What is a contract for Difference or CfD?

December 13, 2022

I was recently asked to explain a Contract for Difference and couldn’t quite give a satisfactory answer. So, I decided to dig a little deeper into what they were and write a blog post to (A) explain my answer in a more satisfactory answer and (B) develop my own understanding of these important mechanisms for renewable energy deployment.

The UK government is concerned with supporting low carbon generation and wants to increase the capacity of low carbon generators in the UK without the public sector (i.e. the government) having to build the generators themselves. However, the private sector will only invest to build a low carbon generator (or any other generator) if it is profitable for them to do so. Typically, renewable energy generators, like wind and solar systems, have high upfront capital costs and low marginal costs, since the fuel for a wind turbine or a solar panel is free. For example, the costs of an offshore wind turbine are highly dependent on a lot of factors, but Catapult gives costs of £2.4 million per MW of installed capacity for an offshore wind farm in 30m deep water. It generally takes a few years of design and construction before the turbine can start producing energy which can be sold, allowing the developer to start getting a return on their investment. It is possible, that during this period the market can change significantly, potentially reducing the value of the energy output of the wind turbine. Additionally, the wind turbine will have to decide where they want to sell the energy. They could enter into an agreement with another party to buy their electricity – known as a bilateral agreement – or they could sell their electricity on the wholesale market. The problem with the former is that the wind turbine cannot guarantee that electricity from the turbine is always available and so they may not be able to find a willing buyer, since it would be much more reliable to agree a bilateral agreement with a dispatchable generator. Selling on the wholesale market however poses further uncertainty for the wind developer, since the wholesale market prices are highly variable.

Contracts for Difference (CfDs) are then used to guarantee the developer a certain price for their electrical output that they would otherwise sell through the wholesale market. The developers enter into an agreement with the Low Carbon Contracts Company (LCCC), a government-owned company which pays a guaranteed flat-rate for the electricity output from the wind turbine over a 15-year period. This guaranteed flat rate – known as the strike price – reduces the uncertainty in the project to the extent that the developer is willing to undertake the construction of the project. Essentially, the strike price provides renewable energy investors with revenue certainty and substantially reduces the risk in the project.

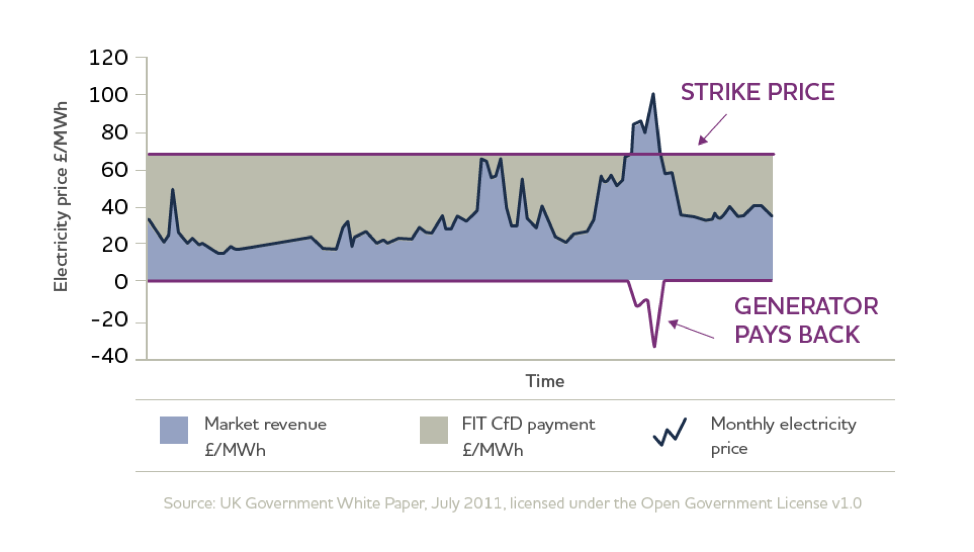

The strike price is the guaranteed income for energy generated. All the energy sold by the generator on the electricity market is compared to the strike price for the duration of the contract. When the electricity price is below the strike price then the LCCC makes a payment to the generator up to the strike price and when the electricity market price is above the strike price then the generator makes a payment of the difference to the LCCC. Therefore, most of the time the LCCC makes payments, which are funded by an additional Levy on all licensed electricity suppliers in GB. However, in times of very high electricity prices (like those we have seen recently), then the LCCC receives payments from the generators which can act to reduce to electricity market prices. The CFD Levy is of course passed on to consumers by the electricity suppliers, so is ultimately borne by the consumers. Figure 1 illustrates how the LCCC is paid back when the market price exceeds the strike price.

When the market price is above the strike price then the generator pays back the LCCC.

The strike price is determined by an auction in which developers submit sealed bids. In this auction, each company bids for a project with a size, strike price and capacity and year of delivery. The LCCC sets an upper boundary for the price that the developers can submit, known as the Administrative Strike Price, so developers can bid for prices up to this level. There is also a total capacity cap on the auction, which sets the maximum amount of capacity that will be supported. The bids are then ordered from low to high and the lowest bids are accepted until the total capacity is reached or all the projects are awarded. The auction is ‘pay-as-clear’, meaning that any project with the same delivery year receives the same strike price. The auctions ran every two years after the first CfDs were announced in February 2015 but this year the government has announced that auctions will be run every year.

To allow for innovative technologies which may be more expensive, the auction is split into pots, with more nascent technologies grouped together in the same pot. For example, floating offshore wind, wave and tidal energy are all much less well developed than fixed-foundation offshore wind so these technologies compete against one another in a different pot with a different administrative strike price and capacity. In the previous auction (completed summer 2022) these technologies competed in Pot 2, while fixed offshore wind was a separate Pot 3 and Pot 1 includes Onshore wind and Solar PV projects. The respective 2022 budgets for Allocation round 4 were £10 million for Pot 1, £75 million for Pot 2 and £200 million for Pot 3.

Once the CfD auction is complete the successful bids are informed and they must provide a Supply Chain plan to show that they are capable of delivering the project. The CfD can then be awarded or terminated. If the project is awarded then the developer is given a Milestone Requirement, which requires to developer to have spent at least 10% of the total pre-commissioning costs on the project or have met the project commitments as set out in the CfD. Applicants that do not sign an awarded CfD or have their CfD terminated may trigger the non-delivery disincentive which bars them from entry into the next CfD auction.